Avalanche Danger Update

Strong winds and snowfall have significantly increased avalanche danger in the Western Chugach Mountains of Chugach State Park. Avalanche danger is expected to remain elevated for the foreseeable future, as active (i.e. stormy) weather is forecast the next few days.

Fresh wind slabs have developed from new snow and wind, and are expected to continue to build in the coming days. Serious persistent slab concerns also exist in many areas.

Dangerous and potentially deadly wind and persistent slab avalanches may fail naturally, and will be especially prone to human triggers.

Please keep in mind that many popular trails and areas in Chugach State Park are exposed to and cross potentially dangerous avalanche terrain. Trails like Powerline (from Glen Alps) and Falls Creek (on Turnagain Arm) are exposed to numerous avalanche paths that regularly avalanche naturally. You could be caught, buried, and killed in an avalanche even if you’re on flat ground in the lower or mid elevations: BE MINDFUL OF AVALANCHE TERRAIN ABOVE YOU!

If you recreate in the mountains during the snow season please make sure you have at least a basic level of avalanche awareness that enables you to identify and avoid potentially dangerous avalanche terrain and paths, practice “safe travel protocols for avalanche terrain,” and effectively use avalanche rescue equipment (beacon, shovel, probe).

Before you head out to recreate, leave a “trip plan” with a friend or family member staying in town to facilitate the initiation of a response in the event of an accident or emergency.

*Click the hyperlinks and icons throughout this page for further learning*

Avalanche Problems:

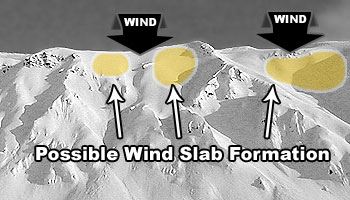

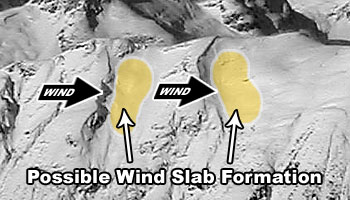

Natural wind slab avalanches are possible, and human triggered wind slabs likely, on steep (35*+) and leeward upper elevation terrain (primarily top-loaded slopes below ridges and cross-loaded gully sidewalls above 2500′). These wind slabs may be up to D2 in size (large enough to bury and kill a person), and will be especially dangerous where the debris is channeled into a “terrain trap,” which greatly increases the consequences of getting caught in a slide, or there is exposure to a dangerous fall.

If you get out in the mountains, be on the lookout for red flags of wind slab danger: recent avalanches, shooting cracks (cracks that radiate out from your feet when pressure is applied to the snow), and heavily wind loaded terrain features that look bulbous and/or feel hollow. Wind slab danger may be sussed out with pole probing and quick hand pits. Convexities are likely trigger points.

Be especially mindful of the potential for wind slabs to fail naturally from above you. Avoid exposure to the paths and runout of such wind slabs, especially as they may trigger larger persistent slab avalanches as they descend. Dangerous paths in this regard exist along the Powerline Trail from Glen Alps, Falls and McHugh Creek and Penguin Ridge trails on Turnagain Arm, the Turnagain Arm trail itself, the upper Crow Pass/Iditarod Trail from Eagle River Nature Center, and upper South Fork Eagle River near Eagle and Symphony Lakes. These are only examples, and there are many other trails that are in or cross potentially dangerous and deadly avalanche terrain in Chugach State Park.

Natural and human triggered persistent slab avalanches up to D3 are possible on terrain steeper than 30* above ~2500′ elevation. Please keep in mind that while avalanches are only expected to be triggered above 2500′, the debris could run out to much lower elevations (even sea level). These avalanches may be triggered naturally by new snow and wind loading, or a smaller wind slab’s debris as it descends a path with more deeply buried persistent weak layers.

Persistent slabs are expected to be most susceptible to human triggering where they’ve been stressed by wind loading and there is a “sweet spot” trigger point where the slab is thinner, and the “stress bulb” emitted by a human more readily penetrates to the buried persistent weak layer.

Buried persistent weak layers responsible for the persistent slab avalanche danger primarily exist in two forms: faceted snow around buried melt-freeze and rain crusts, and large basal facets and depth hoar near the ground. Here’s an observation that provides an example of the persistent slab problem.

In terms of a human triggering a persistent slab avalanche, it could be catastrophic. While a lower probability avalanche problem than wind slabs, they could be extremely high consequence. They are expected to behave like hard slabs, meaning they could allow a trigger to get into the middle of the slab before breaking above and around the trigger making escape especially difficult.

If you’re venturing out into the mountains this week, understanding the persistent slab avalanche problem will take thorough stability assessment and snowpack analysis. Dig a full snowpit, search for and identify buried weak layers, and conduct a stability test like the ECT to better understand slab reactivity. Be on the lookout for red flags like recent avalanches, whumphing (i.e. collapsing), and shooting cracks.

GIVE THE SNOWPACK ON STEEP TERRAIN TIME TO ADJUST FROM THE SIGNIFICANT AMOUNT OF STRESS IT’S RECEIVED FROM RECENT SNOW AND WIND!

Cornices have grown from the recent strong winds and precipitation, and are expected to be especially prone to failing and falling (both naturally and from human triggers). Give corniced ridges a wide berth; they can break off much further back than expected (even beyond where they’re overhung). Never approach the edge of a snow-covered ridge, unless you’re sure it’s not corniced. A cornice fall itself is dangerous, but can also trigger a large avalanche as it “bombs” the slope it falls onto.

Natural cornice falls may result from new snow and wind. These cornice falls could trigger potentially dangerous and deadly wind slabs, and even larger and more dangerous persistent slabs. Some very large and dangerous paths, like the one on Penguin Peak that encompasses the entire Penguin Ridge trail to treeline, could run naturally up to D3 in size as a result of a cornice fall. Such areas should simply be avoided until more stable avalanche conditions exist.

Natural and human triggered loose snow avalanches (aka “sluffs”) are likely on steep (40*+) upper elevation (3000’+) terrain sheltered from the wind (where the snow isn’t wind-packed and remains loose and unconsolidated). While loose snow avalanches will only be D1 in size, they could trigger a larger slab if they build significant mass as they descend. They can also be dangerous around terrain traps and areas with fall exposure; while they may not be big enough to bury a person they could sweep one off their feet. If you find yourself on steep terrain with loose snow this week, practice effective “sluff management” and be mindful of exposure and terrain traps.