Avalanche Danger Forecast

Issued Friday, December 11, 2020 at 6pm for the greater Anchorage area Western Chugach Mountains (i.e. Chugach State Park):

Winds picked up Friday afternoon with modest but widespread snow transport and wind loading observed across Chugach State Park.

Winds in the alpine through at least Saturday are expected to wind load leeward terrain, which will keep the avalanche danger steady to slightly increasing within the moderate range. Fresh wind slabs will develop and existing persistent slabs will be stressed if wind loaded.

In general, the snowpack in southern (closer to Turnagain Arm) and eastern (further in the mountains) zones of the park is deeper and stronger. Western (closer to Knik Arm) and northern (closer to Knik River) zones of the park generally have a shallower and weaker snowpack.

Localized fresh wind slabs on steep, wind loaded terrain and isolated persistent slabs in areas with an especially dangerous snowpack setup (slab + reactive persistent weak layer) are expected to be the two primary avalanche problems.

Avalanche Problems:

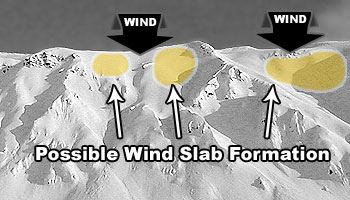

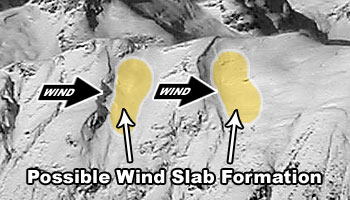

Localized wind slabs up to D2 in size will remain possible through this forecast period on leeward (primarily west through north) aspects above 2500′ where the terrain is steeper than 35º. Potentially dangerous wind slabs are most likely to exist below and along corniced areas and otherwise along the lee sides of ridges and cross-loaded features like gullies (see graphics above).

Recent avalanches, shooting cracks, hollow and/or punchy feeling snow (denser wind-packed snow overlying looser and weaker snow), and pockets of deeper snow (especially with a bulbous appearance) are all indicators of potential wind slab danger.

Pole probing and hand pits are a quick and effective means of assessing this problem as you travel. Use pole probing to quickly feel out areas of denser, wind-packed snow overlying looser and weaker snow. Use hand pits to quickly assess how near-surface layers of snow are bonded.

Digging a snowpit and conducting a compression test and/or extended column test will give you an even better assessment of bonding and instability before you commit to terrain of consequence.

You can also assess wind slab reactivity via smaller and safer “test slopes” that are representative of larger terrain.

Wind slabs have the potential to “step down” and trigger even larger and more dangerous persistent slab avalanches.

Isolated persistent slabs up to D2.5 in size will remain possible through this forecast period on all aspects above 2500′ where the terrain is steeper than 35º. Some terrain features may harbor a hard slab with persistent weak layer where the balance might be tipped this weekend by additional stress from a trigger (human possible and natural unlikely).

While persistent slabs are a lower probability avalanche problem than wind slabs, they are of higher consequence and much less predictable. They are less likely to be triggered than wind slabs but will be larger and more difficult to escape (due to hard slab characteristics).

Diverse and widespread persistent weak layers exist in the snowpack throughout the Western Chugach. Faceted snow exists above and below crusts in some areas, sandwiched between wind packed layers in many areas, and a basal weak layer of advanced facets and depth hoar is widespread.

In addition to red flags of persistent slab danger like recent avalanches, shooting cracks, and collapsing (aka “whumphing“); digging a snowpit and conducting an extended column test will give you a better idea of how this problem is manifesting where you intend to travel.

Terrain management is simply the best way to avoid this high consequence and unpredictable avalanche problem: don’t expose yourself to big, steep terrain capable of producing a large persistent slab.

Dry, loose snow avalanches are possible on terrain above 3000′ where the terrain is steeper than 38º. These may be in the form of naturally triggered wind-induced heavy spindrift or human triggered sluffs where uncosolidated snow has been sheltered from the wind.

While these avalanches will be relatively small (D1), they do have the potential to cause a fall or loss of control and build up mass that “steps down” and triggers a larger slab avalanche.

Don’t let a small loose snow avalanche catch you off guard, especially if you’re on exposed terrain. Here’s a recently released 30 minute film in which a very experienced mountain guide tells the story of losing the lives of two close friends while climbing steep terrain to ski a classic line in the Tetons:

Before traveling on, through, or under terrain that has the potential to avalanche; think about the consequences and have a plan (to escape the avalanche, for re-grouping, and rescue).

Be mindful of terrains traps!

Click the hyperlinks and icons to learn more.

Food for thought: Have you ever thought about the distinction between “natural” and human triggered avalanches? While it conveys a necessary distinction, it implies humans are other than natural. The notion that humans are not part of “nature,” and not enmeshed thoroughly in the natural world, is part of the psychosis of the modern and industrial era. Might there be a better way (that doesn’t contribute to the lingual psychosis of humans as separate from “nature”) to convey the distinction between avalanches triggered by wind, snow, rain, species other than Homo sapiens, etc. versus those triggered by the human animal?