What do you think about big mountain, or wilderness, solo adventures? Are you one to judge: the recklessness, the insanity, the irresponsibility, the stupidity, the carelessness, ad nauseam? Big mountain solo adventures are not something I’d encouraged. I don’t think others that undertake such endeavors would necessarily encourage them either. We’d be disdained for doing so (even more so than for the choice to undertake such endeavors ourselves), and it just doesn’t seem right.

That said, those that do undertake such endeavors typically do so more than once. It’s a powerful and intense experience. The experience is all yours: the decision-making, the processing, and the emptiness of the wilderness that amplifies the magnitude of inner space. I don’t know of anything else that squeegees the third eye in such a way…even psychedelics don’t provide as clear of an experience of inner space and oneness, and yoga and meditation don’t provide the same connection with Nature. Maybe you eventually realize that you’re not really alone on such adventures…be it the oneness, the interconnectedness, or the permeability between this dimension and the innumerable others that can be realized.

Maybe there are other layers of value to these experiences that our curated, comfortably numb, modern-industrial, first-world, consumer-capitalist existence disregards? Maybe it’s value of a primal, spiritual, even evolutionary nature? After all, it’s only in this contemporary blink of humanity’s existence that we’ve lost such a connection to the wilderness that demanded such experiences of us. That is, in the vast majority of our past, such experiences were necessitated by Life and Nature for survival – and often as rites of passage. Maybe indigenous cultures developed such rites of passage as they knew such intense solo experiences in the wilderness were an essential and integral part of our being that, while maybe no longer necessitated by Life, were necessary for a mature human being to understand.

Regardless of all my perhaps silly prose, I undertake such solo endeavors rather frequently – as much out of necessity than out of desire. Necessity, in the sense that I need to get out. The mountains and the wilderness are my therapy. They’re essential to my wellbeing. I feel like those of us that aren’t comfortably numb need such an escape, and the mountains and wilderness provide that for us. For those of us that have been blessed to such a degree as to live in a place like Alaska, it’s easy to “drop out” and get that solace. Given the often hectic schedules of modern man and the balancing act life requires of us, solo is often the only feasible way to get out. Maybe that’s not such a bad thing, especially for those of us that would rather expend our energy in the mountains than on the social effort and constraints necessary to coordinate with partners.

With all that in mind, I set off for the Thompson Pass to Valdez corridor of the Central Chugach Mountains for the last week of March 2019. It was a crazy ideal window: an extended high pressure system that was abnormally warm for that time of year. The warmth meant less pressure gradient, extreme offshore flow, and dreaded wind that often rapes the snow in this corridor. However, warmth also preceded the high. Above freezing temperatures and rain reached up to ~4000′ (most, even very long, daytrip accessible Chugach peaks are below 8000′ and approaches typically start from sea level up to ~2500′). Combined with the intense sunshine of the high, this destroyed the powder on all but upper elevation northerly aspects. On the bright side, the solid crust from the melt-freeze cycle made for very efficient and fast alpine travel with low avalanche danger until later in the day on solar aspects. The relatively high water content snow that did remain dry and wintry, combined with a benign temperature gradient, also created low avalanche danger even on the steepest northerly aspects. So, sun and warmth later in the day were about the only worries (besides the slide-for-life snow before the widespread crust softened).

On the second day of a four day ski-peakbagging binge, I went for the biggest peak in the corridor: Mt. Billy Mitchell. Information on this peak is extremely limited (basically non-existent). In Central Chugach guru Matt Kinney‘s backcountry skiing guidebook, he mentions that he attempted the summit of the true Billy Mitchell (Peak 7217) a few times but did not succeed in attaining it. He knew of no other successful ascents. There is no accurate, firsthand information available online or through any other sources. The only history of a prior ascent I’ve been able to locate at the time of this writing is from a 2011 Mountaineering Club of Alaska Scree (their monthly publication) that states Alex Christie claimed a successful summit attempt in April 2010 in a 19 hour push starting at 2am. No details are provided, and he did not provide a report despite numerous requests from the MCA.

I’m not much for 2am starts. About the earliest I can recall waking up for any big mission in Alaska is 4am, and I don’t think I’ve ever left a trailhead earlier than 6am. I left my truck on the Richardson Highway at ~10:15am in trail runners as I had to cross the shin to knee deep Tsina river due to the aforementioned warm temps and meltdown. Consulting the map in regard to distance and terrain, I figured it would either be a modest daytrip (at least for my level of fitness and experience) or I’d get shutdown by technical difficulties I couldn’t overcome safely without a rope and partner. My predication was accurate. Moving with purpose, but not hurrying, the mission took about 6.5 hours truck to truck. After all, being based in the Western Chugach with MUCH longer and more heinous approaches required to reach big peaks like Billy Mitchell, I wasn’t too worried about time in the relatively “cleanly” accessed Central Chugach.

As mentioned, the journey started with an open water crossing of the Tsina River. Luckily, it was only about shin deep in the morning. Access to the Seal Glacier, which brings one to the base of the north face of the true Billy Mitchell (there’s confusion as to which peak is actually Billy Mitchell as folks have climbed and skied lines off sub-peaks in the area claiming to have climbed and skied “Billy Mitchell”), begins by following a relatively clean creek bed to the “Key to Lisa”: a narrow and steeply walled slot canyon that gets stuffed full of snow and is actually mostly skinnable and skiable at 30ish degrees. It’s a very neat feature.

Lower opening of the Key to Lisa:

Above the Key, one follows low angle (but in some areas still avalanche prone) glades to the moraines of the lower Seal Glacier. Following the glacier up and around sub peaks, one arrives at the base of the true Billy Mitchell’s big north face:

The real climbing begins at this point:

This zone was the most wind-hammered of the four I climbed and skied during the late March 2019 window, and the ambiance was reminiscent of the Western Chugach (rockier and drier). The snow was chalky and firm, and didn’t require Billy Goat Plates for booting as did most booting in the other zones (Crudbusters, Worthington, Port) I visited late March 2019. Crampons and an axe were essential, as a fall on the long and steep access couloir/face to the west ridge would be brutal due to the firm and likely un-arrestable snow and the choke at the base that gives it a degree of exposure.

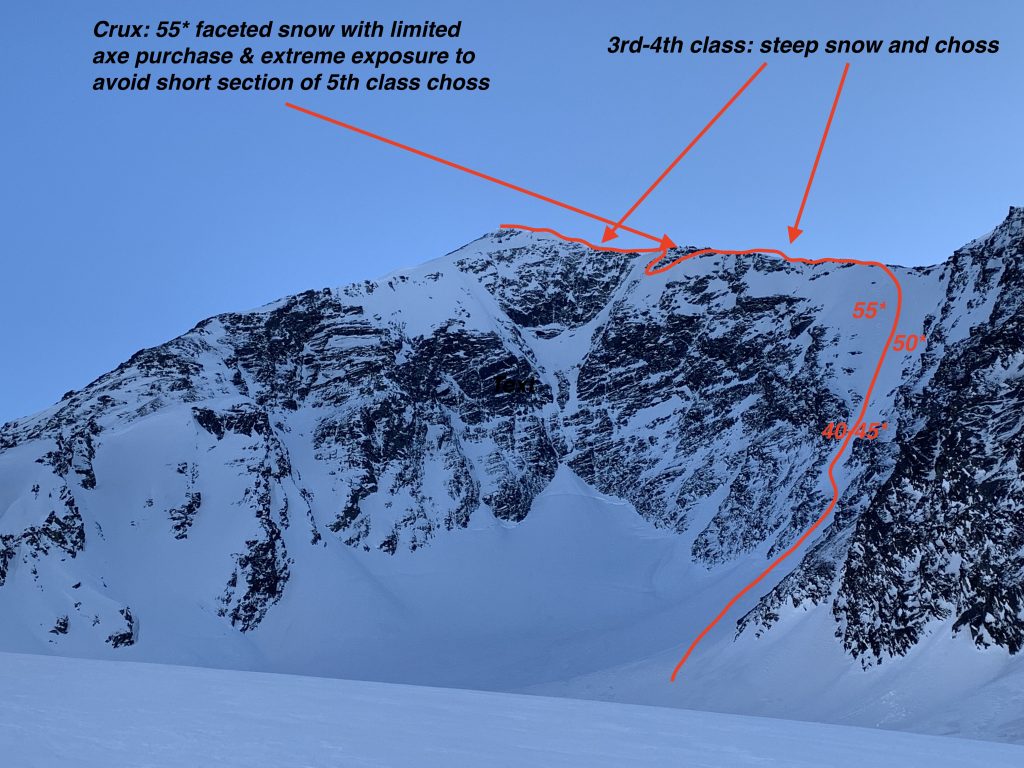

Topping out on the west ridge at ~6700′ provides some rest and relaxation before the Billy Mitchell experience becomes intense again. There does seem to be a skiable line from the summit, but it would be incredibly exposed for the entirety of its very steep ~1400′ and require a long rappel. If not skiing this uber-extreme line from the summit, there’s ~500′ vertical of scrambling up and down the west ridge. Most of it’s 3rd class, perhaps a bit bordering on 4th, with one short 5th class or extremely exposed and steep snow section (see image above).

The extremely steep and exposed snow section where I was forced to leave the crest of the west ridge:

This exposed section is near the top out of the face/couloir. After overcoming this obstacle, it’s a relative cruise up the ridge to the summit. As Billy Mitchell is the highest peak for miles and in a unique zone near the confluence of the Tsina and Tiekel rivers/valley, the summit views are mind blowing:

Returning to the ski drop in for the NE face/couloir, I opted to descend skier’s right of my booter as the snow better and the turns steeper (55* vs 50*):

Blissful low angle glacier gliding followed by near perfect late March corn in the glades had me back at the Key to Lisa in very short order. Later in the day descending the Key to Lisa is another potential crux of this route as the canyon floor was littered with rock, snow, and ice fall. The walls are big and steep and there’s no protection from whatever may fall. On colder, earlier season days with better snow it’s likely no big deal. With hard and icy snow that had not softened at all, debris to maneuver around, and some crater-like openings exposing the creek and its running waterfalls; I had to descend a little slower than I would have liked. While I didn’t notice anything falling while I was in it, likely due to having already been exposed to several much warmer days prior, I was glad to have a helmet (which I also put on for the ascent) and wouldn’t have minded having some body armor.