An outdated computer, and its defunct operating system, is more virus prone and less capable of dealing with an infection than a computer with newer technology and an updated operating system. For an analogy, this is much like how our outdated capitalist society and it’s defunct consumer economy (that is profit-based) is more susceptible to fallout from the novel coronavirus than a post-capitalist and non-consumer society (that is people and planet-based). As I’ve discussed in other trip reports (here, here, and here), the economy rules our being and is very arguably the most existential threat to both the human species and countless other species with which we share this wondrous planet (as the wanton overconsumption and waste of our economical paradigm is driving the world’s sixth great extinction, aptly named the Anthropocene extinction).

COVID-19 is a wake-up call, and perhaps one we needed considering that we were ignoring the gravity of climate change and humanity’s destruction of the biosphere. We humans are absolutely and thoroughly trashing this planet, our one and only home. I’ll go on a tangent here to mention how absurdly ridiculous space colonization of a planet like Mars is. First, if we need to colonize a planet like Mars because we’re running out of resources on Earth and making this planet less habitable, why would any sane person think we have the resources on Earth to make interplanetary colonization feasible and who in their right mind thinks Mars could be made more habitable than Earth?

We have a perfectly good planet right here on Earth. It’s our only home. Whether you’re on the Creationism or Evolutionary side of the spectrum, either this planet was made for us or we evolved as an intricate part of it. Why not save what we have, and what we know is a sure thing (and a very wondrous thing at that)? It’s infinitely more feasible to keep Earth habitable than indulge ridiculous space-colonization fantasies.

So, why is this novel coronavirus a necessary wake-up call? First, it’s grinding to a near halt the capitalist consumer economy that is laying waste to the biosphere. In just a few weeks of slowing the economy the coronavirus has arguably done more to stop the primary destructive force of the biosphere (the modern consumer economy) than the combined total of all the world’s mainstream environmental organizations. I’m willing to make this argument because I see two types of environmental organizations: those that challenge the status quo and those that don’t (the mainstream ones). The radical organizations that challenge the status quo have more or less been rendered obsolete by the Establishment branding them as essentially terrorist organizations. The mainstream environmental organizations that don’t challenge the status quo are part of the problem, as they’ve been assimilated into the capitalist economy and consumer paradigm.

Another reason COVID-19 is, as mentioned above, a necessary wake-up call is that despite how thoroughly dire the climate and environmental crisis is humanity has more or less continued to ignore its severity and refused to acknowledge our fundamental planetary interconnectedness. COVID-19 has made our interconnectedness undeniably apparent. For many of our disappointing world leaders (members of both the Democratic and Republican party Establishment included), COVID has also taken their focus away from the status quo of neocolonial war and exploitation.

For instance, in the past five years, the US-backed Saudi Arabian military intervention in Yemen’s civil war has resulted in an estimated 100,000 deaths. Since the post-9/11 US wars began, there has been a resulting 480,000-507,000 fatalities (mostly civilians in the Middle East). Since 2000, Israel (with US support) has killed more than 10,000 Palestinians (mostly women and children non-combatants). As I write this, there have been 21,191 worldwide deaths due to COVID-19. While COVID-related fatalities are increasing exponentially and rapidly, we’ve got a long way to go before the body count reaches levels similar to those resulting from US imperialism and neocolonialism in just the past couple of decades.

I’ve been seeing a lot of posts on social media urging individuals to make personal sacrifices, like staying at home and even forgoing outdoor recreation with appropriate social distancing because any incidents would further burden already over-burdened public safety and healthcare systems. These posts suggest that these personal sacrifices will allow a return to normalcy sooner rather than later. While we should definitely go above and beyond to follow best practices for COVID-19 protection as recommended by experts, I surely hope we don’t return to “normal” when we come out of this crisis. Normalcy, which is the status quo of consumer capitalism and wage slavery, is destroying both our planet and our souls.

I hope we come out of this public health crisis much wiser and with an enhanced perspective. This public health crisis is an opportunity to reimagine our existence, and it may force us to do that since even the climate crisis couldn’t get us to do so. I encourage you to watch the video below, and hope you’ll join the movement to put forth better ideas for our collective future.

Human beings were not made for wage slavery and endless consumerism. We were not created to work, buy, consume, and die. We are not cogs in a machine. The only labor appropriate for humanity is that of necessity and Love.

We need to seriously reflect on the opportunity this crisis provides. We need to imagine a new way of being human in this world, and refuse to live in fear. It’s time to erase the programming of consumer capitalism. A new world is waiting to be born.

On Sunday, March 22, 2020 Jess Tran and I headed up Winner Creek from the Girdwood Nordic trailhead. With moderate to strong outflow northerly winds forecast as high pressure entered the region from the previous day’s few inches of fresh snow with moderate southerly winds, there weren’t really any expectations other than skiing sheltered pow up Winner Creek and doing more recon for an ascent and descent of Kinnikinnick Mountain (which has been on my ski-peakbagging to-do list for a few years).

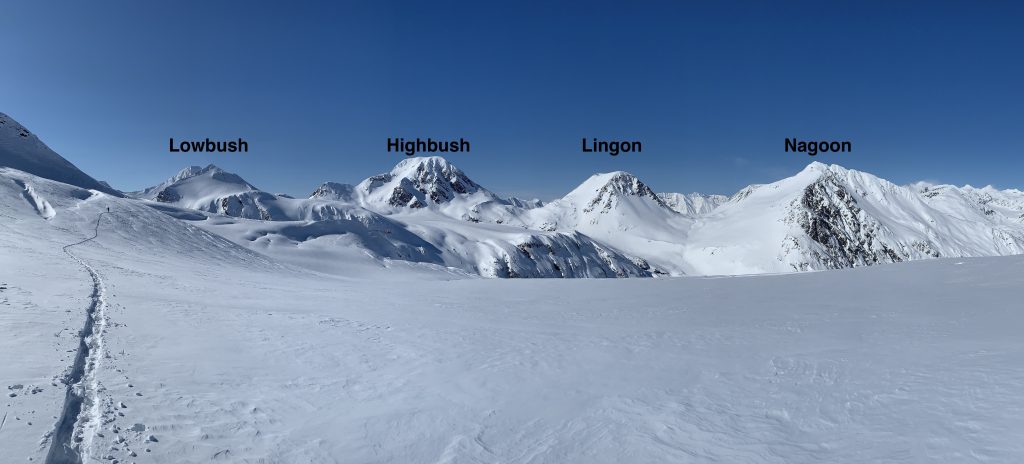

We didn’t get an early start and left the trailhead after 10am. The late start lowered expectations further, as on sunny spring days solar aspects are typically heated up and destabilized by late afternoon. With that in mind, we skinned up to the pass between Lingon Mountain and Highbush Peak.

Jess skinning up from Winner Creek:

Upon arriving at the pass, I could see snow pluming off many peaks in the distance from the increasing northwest wind. However, Kinnikinnick itself didn’t evidence significant snow transport and the west face we hoped to climb and ski was windward and getting modestly stripped of snow rather than loaded. It was also colder than expected at the mid and upper elevations and it seemed like the northerly wind was further cooling upper elevation solar aspects.

Kinnikinnick as seen from the Lingon-Highbush pass area:

We didn’t even bring glacier gear. First, as already mentioned, I didn’t think we’d actually be giving Kinnikinnick a go. Second, Kinnikinnick would be a 17+ mile day with 7000’+ vertical and carrying a glacier kit for that distance would have added to the beatdown. Third, given my experience with coastal Chugach glacier travel, I don’t really think it’s necessary when visibility is good and the full topography of a glacier can be seen. After all, I’ve never seen an alpine coastal Chugach glacier with less than ten feet of dense maritime snow coverage by spring.

Considering plenty of daylight left despite our late start and the solar slopes of Kinnikinnick being windward and cooled by the northerly wind, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to take a closer look. It’s a considerable slog, even from the Lingon-Highbush pass, over heavily glaciated terrain (Punchbowl, Rosehip, and Kinnikinnick glaciers) and I still wasn’t committed other than having a closer a look.

Mat skinning across the Rosehip glacier toward Kinnikinnick:

Kinnikinnick as seen from the SW on the glacier traverse approach:

The Western Chugach “Berry Peaks” as seen from the Rosehip glacier:

Things continued to line up, and soon we had completed our few mile glacier traverse (at or slightly above the Highbush-Lingon pass elevation) to the base of Kinnikinnick’s west face. From there, realizing even more clearly the extent of the west’s face recent shed (of loose snow avalanches without any resulting slabs), we felt comfortable with stability and began the climb. I pride myself on skintrack aesthetics, and made a few elegant Z’s up the west face before transitioning to booting. The booting was deep and Billy Goat plates for flotation would have been nice and greatly enhanced efficiency, but I was glad I hadn’t carried them for several miles for a relatively short section of calf to thigh deep booting.

Jess skinning up the lower west face:

Jess booting the upper west face:

Arriving at a small col on the north ridge a couple hundred feet below the summit, I realized the extent to which satellite imagery misrepresented the final ridge climbing section to the summit. Looking up at a giant, icy, and exposed gendarme followed by more rimed-up and extremely firm exposed snow climbing; I initially balked (especially considering that I’d only brought a lightweight aluminum ax and not a proper alpine tool). Nonetheless, I was determined to search around for a feasible route to the summit having traveled this far and being this close.

Surely enough, I was able to downclimb and go below and around the icy gendarme. That put me in an even better position for the few hundred feet of climbing to the summit: while I still would have to climb extremely steep and firm snow and rime that was very exposed, there was a path that was less technical than navigating through the several mini, ice-covered gendarmes that initially presented upon arriving at the col. A final knife-edge snow ridge brought me to a nice summit with enough room to relax for a bit.

Mat climbing around the icy gendarme:

Mat ascending the north ridge:

I down climbed back to col, where Jess had waited in a windless and sunny spot with outstanding views, and we readied ourselves to ski the line. The entrance was skinny and VERY steep, but luckily the sun crust from the prior day had softened a bit. We re-grouped a few hundred feet below the entrance underneath a rock band, and from there we descended about 1500′ to the icefall.

Looking up at the line from above the icefall:

Jess ready to descend the Kinnikinnick icefall:

I didn’t want to re-trace our initial convoluted glacier traverse approach, and felt comfortable descending the icefall based on satellite imagery research and looking at it closer earlier in the day on the approach. We decided to take the skier’s right side, and this provided a great egress through incredibly aesthetic terrain to the lower valley (Rosehip Creek) that feeds into the west fork of Twentymile. The total descent from the col on Kinnikinnick’s north ridge was over 3000′ (definitely one of the most aesthetic runs I’ve ever made).

Looking back up at our tracks on the climb back up to Lingon-Highbush pass:

From the valley, it was a ~2000′ climb back up to Lingon-Highbush pass. After which we had a typically exquisite 2000’+ run back down to the Winner Creek trail. Chugach Powder Guides loves this run, and they typically farm the hell out of the protected powder in this glaciated hanging valley. This adventure was made all the more surreal by COVID-19’s elimination of heli-ski traffic. No noise pollution. No carbon-gluttonous heli-recreationists. A sublimely beautiful and completely un-tracked Western Chugach valley with a deep wilderness feel.

Jess climbing back up to Lingon-Highbush pass:

A few miles of skinning followed by a couple miles of skating, double-poling, and a final rip of recently groomed nordic corduroy put us back at the trailhead in a little over 11 hours. This day was an exceptional blessing from the Chugach, for which I’ll be forever grateful. We love the Chugach!