Avalanche Danger Forecast

Issued Tuesday, December 8, 2020 at 12pm for the greater Anchorage area Western Chugach Mountains (i.e. Chugach State Park):

A few to several inches of new snow Tuesday and Wednesday, combined with moderate to strong winds, will increase avalanche danger.

As snowfall tapers off and winds lighten, avalanche danger is expected to decrease.

While the snowpack in southern and eastern zones of the park is generally deeper and stronger, these areas will experience more snow and wind Tuesday and Wednesday. The added stress from more new snow and wind loading is expected to create more dangerous avalanche conditions in southern areas closer to Turnagain Arm and eastern areas that are deeper in the mountains.

Western and northern zones of the park generally have a shallower and weaker snowpack, but have been less affected by recent snowfall and winds.

Steep, heavily loaded leeward terrain and steep, northerly aspects in the upper elevations are expected to be the most dangerous in regard to the two primary avalanche problems: wind and persistent slabs.

Avalanche Problems:

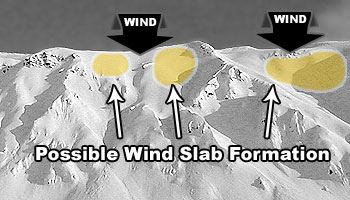

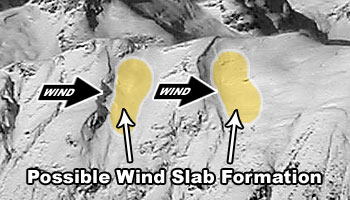

Wind slabs up to D2 in size are likely Wednesday and possible Thursday and Friday on leeward (primarily west through north) aspects above 2500′. Potentially dangerous wind slabs are most likely to exist on the lee sides of ridges and cross-loaded features like gullies (see graphics above). Expect wind slabs below and along corniced areas.

Leeward terrain steeper than 30º will be prone to both natural and human triggered wind slabs Wednesday due to ongoing wind loading from moderate to strong winds and the chance of continuing snowfall (higher likelihood of more snow in southern and eastern zones of the park). Thursday and Friday wind slab danger will decrease, but human (and other animal) triggering will remain possible on terrain steeper than 35º.

Recent avalanches, shooting cracks, hollow and/or punchy feeling snow (denser wind-packed snow overlying looser and weaker snow), and pockets of deeper snow (especially with a bulbous appearance) are all indicators of potential wind slab danger.

Pole probing and hand pits are a quick and effective means of assessing this problem as you travel. Use pole probing to quickly feel out areas of denser, wind-packed snow overlying looser and weaker snow. Use hand pits to quickly assess how near-surface layers of snow are bonded.

Digging a snowpit and conducting a compression test and/or extended column test will give you an even better assessment of bonding and instability before you commit to terrain of consequence.

You can also assess wind slab reactivity via smaller and safer “test slopes” that are representative of larger terrain.

Wind slabs have the potential to “step down” and trigger even larger and more dangerous persistent slab avalanches.

Persistent slabs up to D2.5 in size are possible on all aspects (especially northerly aspects with weaker snow) above 2500′.

Natural and human triggered persistent slabs will be possible on terrain steeper than 30º Wednesday, as the snowpack is expected to be at the peak of its disequilibrium and instability in terms of adjusting to added stress from recent snow and wind loading.

Human (and other animal) triggering of persistent slabs will remain possible on terrain steeper than 35º Thursday and Friday.

While persistent slabs are a lower probability avalanche problem than wind slabs, they are higher consequence and much less predictable. They are less likely to be triggered than wind slabs but will be larger and more difficult to escape (due to hard slab characteristics).

Wind loading and new snow are stressing existing persistent weak layers, which are diverse and widespread. Faceted snow exists above and below crusts in some areas, sandwiched between wind packed layers in many areas, and a basal weak layer of advanced facets and depth hoar is widespread.

In addition to red flags of persistent slab danger like recent avalanches, shooting cracks, and collapsing (aka “whumphing“); digging a snowpit and conducting an extended column test will give you a better idea of how this problem is manifesting where you intend to travel.

Be especially wary of areas that may harbor larger and more contiguous slabs.

Terrain management is simply the best way to avoid this high consequence and unpredictable avalanche problem: don’t expose yourself to big, steep terrain capable of producing a large persistent slab.

Dry, loose snow avalanches (aka “sluffs) are possible on wind-sheltered terrain above 3000′ where the terrain is steeper than 38º.

While these avalanches will be relatively small (D1), they do have the potential to cause a fall or loss of control and build up mass that “steps down” and triggers a larger slab avalanche.

Don’t let a small sluff catch you off guard, especially if you’re on exposed terrain.

Before traveling on, through, or under terrain that has the potential to avalanche; think about the consequences and have a plan (to escape the avalanche, for re-grouping, and rescue).

Avoid terrains traps!

Click the hyperlinks and icons to learn more.

Food for thought: Have you ever thought about the distinction between “natural” and human triggered avalanches? While it conveys a necessary distinction, it implies humans are other than natural. The notion that humans are not part of “nature,” and not enmeshed thoroughly in the natural world, is part of the psychosis of the modern and industrial era. Might there be a better way (that doesn’t contribute to the lingual psychosis of humans as separate from “nature”) to convey the distinction between avalanches triggered by wind, snow, rain, species other than Homo sapiens, etc. versus those triggered by the human animal?