As I sit here in a cheap Salt Lake City hotel writing this trip report after skiing and peakbagging several ranges in the Canadian and American Rockies (Bow, Mission, Bitterroot, Swan, Rattlesnake, Sapphire, Gallatin-Hyalite, Teton, Wasatch) in the past couple months, I feel like I’ve satisfied much more of my curiosity and further reaffirmed that the Chugach is the greatest and mightiest range on the planet. Furthermore, I’ve realized that The Greatland is really the greatest land. Socially, politically, culturally, ecologically, spiritually, etc. the Last Frontier is the future and the United States’ greatest asset.

To provide some evidence of Alaska’s greatness and uniqueness: while the indigenous people have it rough, and future generations will continue to struggle with deep psychological and spiritual wounds inflicted by decades of historical trauma, they haven’t been exterminated or forced to relocate to reservation wastelands like their counterparts in the aptly named “Lower 48.” They play a significant role in Alaskan economics and politics (as they should), and their sociocultural heritage is visible in everyday Alaskan life (as it should be). I thank the Creator(s) for this, as the Alaskan indigenous peoples’ worldviews (and teachings transmitted directly from The Greatland they lived symbiotically with for millennia and have generously shared with the so-called “civilized” world) have provided me with more wisdom and enlightenment than science or any organized religion (western or eastern). The indigenous peoples of Alaska will surely lead the way in regard to The Greatland’s inevitable transition to a post-carbon and post consumer-capitalist society in the coming decades.

More evidence: having spent a month in Montana, faced with striking culture-shock of that state being the least diverse “whitest” place I’ve ever been, my sentiment has been reinforced that the public schools of Alaska’s sociocultural capital (Anchorage) are perhaps the most vivid example of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech coming to fruition. That said, we still have a lot of work to do. As the Reverend and Doctor stated: “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” All of my experiences in Life and America suggest that The Greatland is the most fertile ground for Justice.

Driving through the concrete jungle that is Salt Lake City (as well as the rural highways of the American West) I’m thankful that, while Alaska has become increasingly susceptible to American homogeneity and consumerism, it’s a relative respite from billboards, crass commercialism, and over-development. Perhaps more than anything, this trip has made me realize how deeply in love I am with Alaska: that bipolar bitch of a lover that swings me helplessly from the most ecstatic highs to the most depraved lows and has spoiled the rest of North America for me as nothing more than a short term fling and resounding “meh.”

The last thing I was reading before writing this trip report was renowned American ski-mountaineer Andrew McLean’s “The Chuting Gallery.” Compiling media for this trip report, despite that media being summer photos and videos, I couldn’t help but fantasize about the endless ski-mountaineering lines of the Central Chugach I was noticing. The Wasatch, while beyond beautiful and special, is but a tiny corner of the Chugach. But, enough with this Romanticism, and on with the trip report.

On June 26, 2019 between guiding gigs based out of McCarthy, AK, I squeezed in a trip to the Central Chugach for peakbagging and visiting a good friend: Alaskan wilderness climbing and skiing guru Taylor Brown. I’ve got to mention how interesting I find it that backcountry tourists drop thousands of dollars to come AK and do expensive (and carbon intensive) fly-in trips to the various roadless national parks, while the Central Chugach remains an empty, road-accessible void of state land. Thrice throughout the summer of 2019 I found myself comforted by the Central Chugach’s embrace after fly-in trips to Wrangell-St. Elias, Lake Clark, and Gates of the Arctic National Parks. Despite the expense required to get to these remote roadless areas, it was the easily accessible Richardson Highway Central Chugach where I found the most unmatched freedom and solitude.

Little information is available in regard to Central Chugach adventuring, especially in the summer when the heli-ski companies aren’t operating and offering their uber-expensive and carbon-gluttonous services. As detailed in other Central Chugach trip reports, often unscrupulous heli-ski companies have set a dangerous and unsustainable economic precedent for Central Chugach adventure tourism. That’s got to change. While it’d be more than a stretch to consider any change or transition likely to come in the near future truly sustainable, relatively sustainable ecotourism is a niche that the greater Valdez area needs to tap if the area is to have any longevity in terms of modern human settlement. After all, the road (Richardson Highway) through the Central Chugach is only well-maintained due to it being a national interest tied to the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. Will the road wane, and be closed, along with the pipeline? I hope not; the area should be recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its wilderness value and preserved for future generations’ recreational enjoyment.

Central Chugach locals and Alaska lovers like Taylor Brown and Lance Breeding have been doing what they can (perhaps unknowingly) to make this visionary notion a reality by re-establishing and maintaining historical alpine access trails in the area. Taylor’s Cracked Ice trail has been featured in another Central Chugach trip report, and Lance has put in a ton of single-handed work on the Boulder Creek alpine access trail (click here for GPS via Peakbagger) used to access the area of this trip report. Both such trails access endless Alaskan alpine wilderness and provide a portal to the best and wildest road-accessible trekking, peakbagging, and mountaineering in the world.

Boulder Creek valley at treeline via Lance’s restored mining trail:

Lance’s trail, upon reaching the alpine, continues up the east fork of Boulder Creek and is marked by cairns. For this trip, I left the trail at the base of the north ridge that leads to Peak 4970 and Mt. Tiekel:

After passing Peak 4970, the upper east fork of Boulder Creek and north face of Mt. Tiekel come into view:

The north ridge of Tiekel is a sublimely pleasant early summer snow climb:

Being my 14th summer in Alaska, the summer of 2019 seemed like the one with the most thunderstorms (and one can be seen building in the below photo). I chatted with longtime McCarthy residents about the unprecedented June and July thunderstorms that built up almost daily over the Kennicott and Root Glacier area peaks before drifting down to the lowlands of the Nizina and Chitina River valleys. This migration of thunderstorms from the Wrangell Mountains into the low valleys is something that has rarely, if ever, happened prior to summer 2019. Powerful thunderbolts struck directly overhead Taylor’s cabin (near the confluence of the Kennicott and Nizina Valleys) several times throughout the summer.

The summer of 2019 was definitely the smokiest. July into August I drove from Valdez to McCarthy to Anchorage to Fairbanks and back to McCarthy (making a huge loop through the central portion of the state) and the wildfire smoke was inescapable. An equivalent, for scale and comparison sake, would be the entire intermountain West (ID, MT, WY, UT, and CO) being engulfed in smoke. Add to that the reports of salmon dying from overly warm water on the great rivers of Alaska, and it becomes appalling how many Alaskans and Americans are burying their heads in the sand when it comes to acknowledging the increasingly undeniable reality of anthropogenic climate change.

View north (down the Tiekel River valley) from the summit of Mt. Tiekel (with the initial dark buildup of a thunderhead that would produce a powerful but short-lived afternoon storm):

View west from the summit of Tiekel (with high passes between east and west forks of Boulder Creek visible):

Three Pigs as seen from the summit of Mt. Tiekel:

From the summit of Tiekel, it’s an easy hike down the south face-ridge to the col between Tiekel and Peak 6504. From there, great hiking up the north ridge of 6504 leads to the summit. The views from this summit are even better!

Peak 6504 north ridge from Tiekel south face-ridge descent:

View from the summit of Peak 6504 into Stuart (left of center prominent valley) and east fork Boulder Creek (center right prominent valley) drainages:

View west from the summit of Peak 6504 (Stuart Creek is the valley in center of photo which has another alpine access trail maintained by neighborhood locals that will be detailed in a future trip report):

View south from the summit of 6504:

View up the Cleave Creek glacier valley (center of photo) from the summit of 6504:

Three Pigs from 6504 summit:

From the summit of Peak 6504 I returned to the col between it and Tiekel and had the best glissade of my life down the large west-facing gully into upper east fork Boulder Creek:

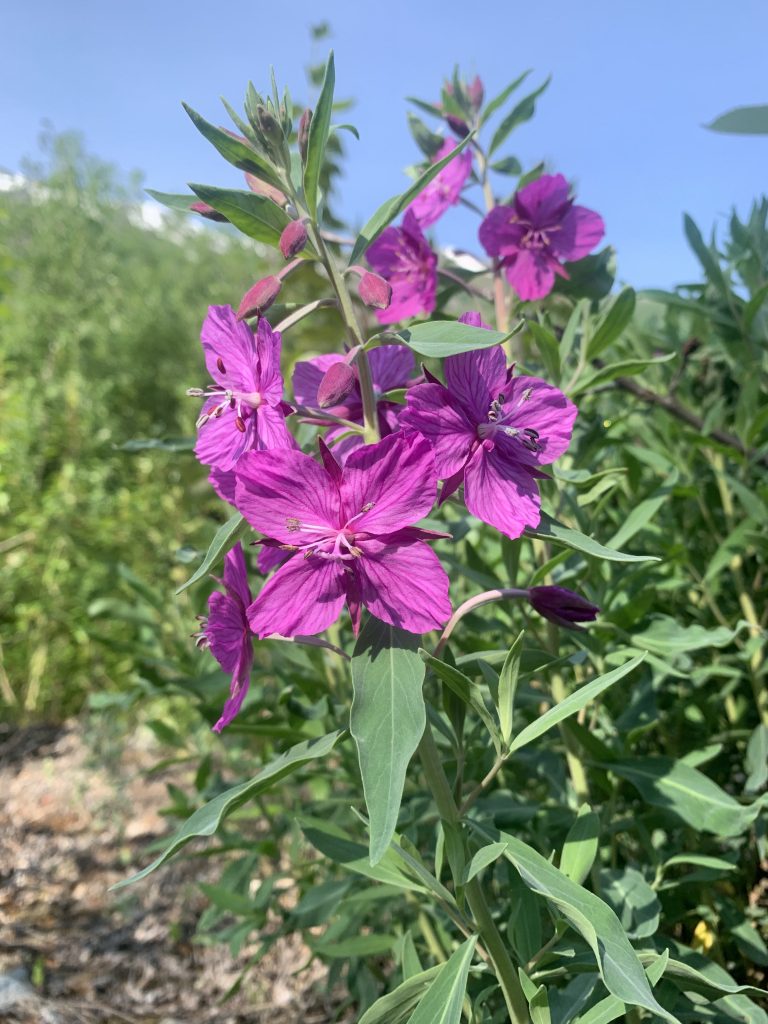

One thing about the extremely sunny, hot, and dry summer of 2019 is that it produced insane wildflower growth throughout the state. I documented more than a dozen varieties on this trip alone. I will include other wildflower documentation (like the incredibly rare Lady Slipper orchid found at the base of Donoho Peak in the Wrangells) in future trip reports. I will also make an effort to update the below photos with species ID when I make it back to AK, and have Verna Pratt’s book handy.

In closing, the words of Derrick Jensen ring loud and clear when considering these Alaskan wildflowers: “I know commercials for products I will never use better than I know birdsongs I hear at dawn and dusk. How could I possibly expect to integrate myself as a citizen into the community I at least call home if I can’t be bothered to learn even their spoken or sung languages?” It’s a testament to the homogenizing power of modern America’s capitalist sociocultural programming that we know more about consumer products than the ecology of our own localities.