Without Mirrors

What distinguishes humans from “the other” animals? We are animals, for sure. As I’ve often levied the accusation that we are in fact the least intelligent species (because we are the only one so wantonly destroying not only our own habitat but the entire biosphere), this question often crosses my mind.

As I was daydreaming deep in the mountains the other day (a place of Natural, not manmade, creation where the veil is thinner), a new distinguishing feature came to mind in a roundabout way: it’s our narcissism that distinguishes us a species. I say it came in a roundabout way because the stream of consciousness involved observing the lovely local ground squirrels (whose exceptional cuteness redeemed them for destroying a drybag and putting a dozen small holes in a relatively new tent).

Do such animals have a sense of self and, if so, how is it formed? Well, they don’t have mirrors (and obviously no picture taking or video recording devices). This made me imagine a life without mirrors (or any apparatus through which we see ourselves). Without such self-reflecting devices, nature provides only very rare instances through which we’d be able to observe ourselves – such as a calm day at a reflecting pool of clear water (as Narcissus did in mythology). But what are the chances that the stars align for such an opportunity to see ourselves (and it seems doubtful taking advantage of such an opportunity would even be in our consciousness)? Suffice to say, we might never really see ourselves reflected back at us in a meaningful way.

Stop and take a second to process the profound and revolutionary implications for consciousness that this has: the implications for sense-of-self, self-image, and ego of living without mirrors. Without mirrors, we would only know ourselves (and the world) through “the other.” Without mirrors (which I’m using as a catch-all for anything that reflects one’s image back at oneself), our eyes only take in and our brains only process “the other.” How fundamentally different would our sense of self be if we never saw our self, but instead could only know ourselves and the world through others?

Here is the crux: considering these profound and revolutionary implications for self-knowing that I’ve mentioned, it seems there would be no “other.” Our consciousness (without mirrors) seems like it would be incapable of processing “other” the way in which normative, contemporary Western human consciousness does.

What I’m referring to as normative, contemporary Western human consciousness is a (relatively infantile) form of human consciousness very unique to modern, industrialized Western societies and the humans that compose them. The basis of this iteration of consciousness is separateness. The individuality and individualism that is foundational to this form of consciousness views everything except its skin-encapsulated ego as “other”:

“A human being is a part of the whole called by us ‘Universe’, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts, and feelings as something separated from the rest – a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.”

As Atomic Al stated so eloquently, the ultimate reality is not separateness; it’s connectedness.

“When we look at the ocean, we see that each wave has a beginning and an end. A wave can be compared with other waves, and we can call it more or less beautiful, higher or lower, longer-lasting or less long-lasting. But if we look more deeply, we see that a wave is made of water. While living the life of a wave, the wave also lives the life of water. It would be sad if the wave did not know that it is water. It would think, ‘Someday I will have to die. This period of time is my life span, and when I arrive at the shore, I will return to nonbeing.’

These notions will cause the wave fear and anguish. A wave can be recognized by signs — beginning or ending, high or low, beautiful or ugly. In the world of the wave, the world of relative truth, the wave feels happy as she swells, and she feels sad as she falls. She may think, ‘I am high!’ or ‘I am low!’ and develop superiority or inferiority complexes, but in the world of the water there are no signs, and when the wave touches her true nature — which is water — all of her complexes will cease, and she will transcend birth and death,” – Thich Nhat Hanh

I encourage you to “touch the water.” While in this lifetime it’s unlikely that we are going to truly escape the prison that is normative, contemporary Western human consciousness, we can gift ourselves with occasional and ecstatic conjugal visits with other (more enlightened) forms of connectedness-consciousness. Plus, as I’ve discussed in another trip report, normative, contemporary Western human consciousness is beginning to breakdown.

Binarism is dying, and we are slowly but surely evolving into an age of trans-non-conformity. In our lifetimes, we each can help tear down the prison walls in our own way in order to build a more connected, holistic, and sustainable consciousness and reality for our progeny. We must recognize that our current reality, the modern and industrialized way of being human in this world, is just a phase – and one that must be very short-lived (relative to the entirety of human existence) if we are to survive as a species. Much more evolution awaits the human species if it’s able to overcome its currently imprisoned consciousness and enchained reality. Perhaps the best first act of resistance would be to free ourselves from the shackles of consumer capitalism, its mindlessly immeasurable wasting of Earth’s natural resources, and its delusionally destructive ideology of infinite growth on a planet with finite resources.

Peak 5800, The Unicorn, & Trident

In early June 2020, I made my third trip from Crown Point into the Kenai Mountains’ Falls Creek valley. A few years ago, I made my first trip up there to climb Helios and Solars (as reported here). In early May of 2020, I made my second trip to climb and ski Peak 5800. On a third trip, in early June 2020, I hoped to climb the only other 1000’+ prominence peak (The Unicorn) in the Falls Creek valley as well as exploring deeper in the range towards the Snow River from this alpine access point in order to climb other big peaks (Trident, Jokulhlaup, and Mile Pile).

Conditions in early May for climbing and skiing 5800 were interesting. I was hoping the lower valley floor would still have plenty of snow for easy travel by ski, but it was patchy and thin at the start. Nonetheless, there was enough snow for travel via ski and a melt-freeze crust with low brush made for relatively easy travel (better than walking, at least). Once into the upper valley above 2500′, the snowpack was significantly deep and it became apparent the afternoon corn skiing would be excellent.

I was unsure how to summit Peak 5800, considering its lack of history and that I was climbing the peak with a significant snowpack and plans to ski it from the summit. From my prior trip up Falls Creek, map, and satellite imagery research; I knew I’d likely need to approach it from the back (east) side considering the steep and massive relief on its south side from the valley floor (2800’+ of very serious avalanche terrain) and that west and north aspects were guarded by very steep and difficult to access terrain.

The east side access was initially quite efficient, as I headed up valley to the NE from Falls Creek and eventually wrapped around to the NW. I was at the base of the mountain’s upper 1000′ of steep terrain on all sides here and while the east ridge was dry and seemed like it would be the way to ascend sans snow, I wasn’t fond of wrangling a long stretch of somewhat steep and exposed Kenai knife-edge ridge choss in ski boots. Thus, I opted for steep snow chutes up the SE face.

While I’d maintain that this was the best route option given the circumstances, the snow was already nearly isothermal on this early to thaw aspect and it was a struggle to skin and boot up this 800′ of steep terrain. Lower down on the SE face there was no option but wallowing through isothermal mank in the snow chutes themselves, but up high I opted to link up dry rock bands on which I could scramble more efficiently. I connected to the summit ridge a short distance from the top.

The steep SE chutes would be a fun descent in better conditions, but I wasn’t keen on jump turning down that much isothermal mank with my super lightweight spring ski setup. I had eyed a line on the more due southerly aspect on the way up from the valley floor and figured I’d give this one a shot, as it seemed like it would provide better corn and was a longer and more direct descent line. It turned out to provide a great ~2500′ of fall line 30-40º corn. More mellow, but exceptionally smooth, corn brought me back to the valley floor and I was then employing all sorts of interesting techniques to get back to the Falls Creek ATV trail while keeping skis on and in descent mode. The walk down the ATV trail required a bit of WI2 avoidance given the spring runoff, but otherwise was an easy finish to the day.

Peak 5800 south face ski descent line as seen from The Unicorn summit about a month later:

Just a bit more than a month later, Jess Tran and I headed back to Crown Point for a multi-day trip to climb and explore sans skis. The Peak 5800 trip had provided me with an ascent line up The Unicorn that seemed a lot more reasonable than previous route options I’d considered before seeing aspects of The Unicorn that I was able to glass from 5800 on the May trip.

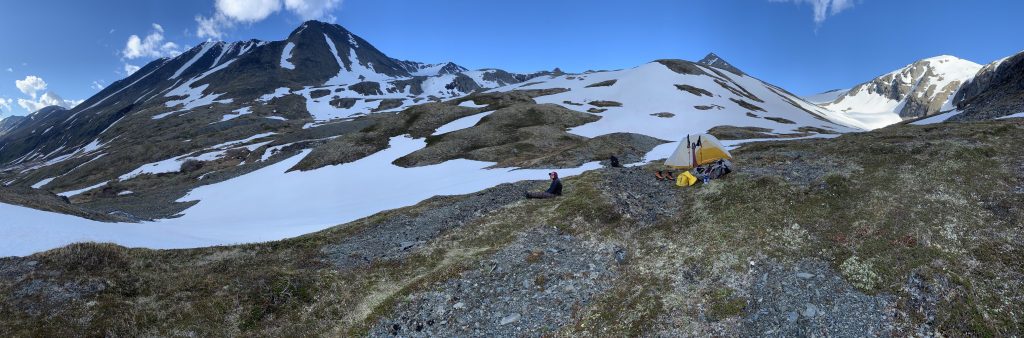

Falls Creek camp below The Unicorn:

We camped around 3200′ next to Falls Creek on day one and, after dinner, I scrambled up The Unicorn climbing the third class north ridge of a 4700′ sub-peak that sits along the east ridge of The Unicorn. At ~4500′ I left that north ridge and traversed a snowfield (shown on the USGS map) to gain The Unicorn’s east ridge at ~4700′ where it makes its final climb to the summit. About a quarter-mile of more third-class scrambling and I was on the summit with incredible Kenai views in all directions.

The Unicorn summit view south:

The Unicorn summit view north  at Peak 5800:

at Peak 5800:

Trident from The Unicorn’s summit:

The next day Jess and I headed up to the pass at the top of the Falls Creek valley and dropped NE down big, steep slopes to the creek that is the most prominent drainage to Ptarmigan Lake. We set up camp around 2600′ to the WNW of Trident’ summit below its beautifully glaciated west side. With questionable weather, as Kenai murk was blowing in and out, we headed up valley to the prominent pass between Trident’s north ridge and Mile Pile.

Looking back at The Unicorn from Falls Creek pass:

Views east from Falls Creek pass:

Weather and visibility improved as we reached the pass and, at this point, I’d decided to at least give Trident a go. Given the heavily serrated summit ridge, questions as to which gendarme was the true summit, and no beta; I wasn’t committed or confident about summiting. Satellite and map research combined with my monocular observations from The Unicorn’s summit the day before and Peak 5800’s summit in early May seemed to make the NE ridge the most reasonable and viable option.

Jess heading up to Trident pass:

Jess at Trident pass (Jokulhlaup Peak above her to the left):

Donning glacier gear, Jess and I traversed SE up and across Trident’s north glacier. While the NE ridge definitely looked reasonable (at least until up near the summit gendarmes), it wasn’t very direct – especially when considering that the NE face had beautiful couloirs that lead much more directly up to the potential summits and their snow conditions were great for booting. Given my penchant for steep couloirs and the efficient snow conditions, we decided to boot straight up. Other than one mega crevasse that runs across the upper north glacier which the runout of the NE facing couloirs are somewhat exposed to, everything was filled in and we were able to boogie up to the summit ridge at 6000′.

Accessing Trident’s north glacier a short distance above the pass:

Jess at the top of the north couloir that we climbed to access the summit ridge:

Unfortunately, it became obvious the broader and easternmost potential summit I’d scoped from The Unicorn was not the top. I initially balked at continuing along the summit ridge to the west, considering the mixed conditions along the very exposed knife-edge ridge and that the highest looking gendarme seemed to require fifth class climbing up notoriously loose Kenai choss. However, having come this far, I decided to at least have a closer look.

Jess and I climbed fourth class mixed conditions along the ridge with our ice tools around a significant gendarme and to the top of a second, which provided just enough standing room for both of us. From here I could more closely examine the seemingly highest one, and true summit, more closely. It was a very steep pinnacle. Sanity would definitely be in question if continuing further (and after returning home and discovering the first ascensionists’ report, found out they had the same feelings). Given that I was undecided and initially thinking I wouldn’t go further, Jess turned around and began the climb back to the top of the NE facing couloir that provided a reasonable spot to relax on a broader area of the ridge.

View north from the gendarme where Jess turned back:

View of the summit gendarme from the east:

I thought I was done too, but having come this far and being this close to such a prominent and beautiful Kenai summit I was spurred on to at least take a look at the summit gendarme’s south side (which was an engaging proposition). This required downclimbing ~50º snow on the south face, scrambling across a fourth class rock band, and then climbing up more ~50º snow to the base of the steep rock on the south side of the summit gendarme. From this point, it was still very questionable if it’d go without a sincere death wish but I eyed a linkup of narrow ledge systems that seemed do-able especially if I could find an anchor from which to rap down.

Looking up at the technical rock section above the steep, exposed, and snowy south face:

I anchored my pack with a screw into ice at the base of the rock band and began the spooky 4th-5th class climbing above the 1500’+ of steep snow and exposure on the south face with my 30m coil of rope. Surely enough, I made it to the top. Finding a suitable anchor on such a precarious gendarme with such questionable rock was a challenging endeavor, but one was located and I delicately rapped back to my pack with the 30m rope being just right for getting back on the snow. I reversed route back to Jess at the top of the couloir and we plunged-stepped and glissaded back to the glacier with an uneventful but beautifully sublime hike back to camp.

Mat heading back along the ridge:

Jess heading down from Trident pass:

Sleeping-in the next morning I awoke to pee and seeing that a thick murk had set in, moved our gear under the tent’s rainfly in anticipation of precipitation. Sure enough, the rain came and we were tent bound for about 20 hours as it poured. After the rain stopped and we had made it through that powerful session of low sensory stimulation wilderness therapy, where the mind has only itself to feed on, we set off through heavy residual murk up 1500′ of steep tundra slopes to the pass and back to the Falls Creek trailhead.

Trident Peak (6050′, 3600’+ prominence) was first climbed on July 1, 1969 by Bob Spurr and Charles McLaughlin via the NE ridge. This trip report is from the second known ascent of the peak, and the first known ascent of the north face.