Dr. FRangeLove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Exposure

The BRO (Bird Ridge Overlook) north face is a ski descent I contemplated for years, after first noticing it on a summer backpacking-peakbagging trip into “Bird Country”: one of the most spectacular zones in the vast Chugach State Park (CSP). Being in the Turnagain Arm area of CSP it has a relatively deep snowpack for the park (at least in the upper elevations), and the north face usually holds snow well into summer.

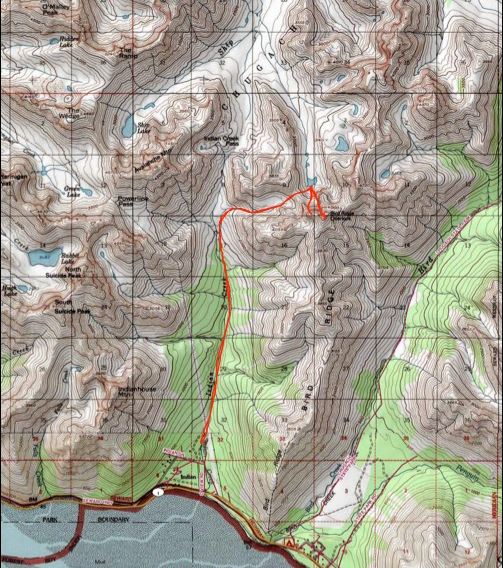

It took a couple snow seasons, after first noticing it on that summer trip, before I was able to figure out this line’s approach. Initially, I was fixated on a long and daunting approach from Glen Alps through Ship Lake Pass (between the Ramp and Wedge) and up the valley with Ship Creek’s eastern headwaters. This proved a challenging option in regarding to timing – in terms of being able to hit it when there’s enough daylight for the long mission, but enough darkness and cool enough temperatures to prevent a long slog through rotten snow on the exit.

After a couple seasons with the line on my mind, Southcentral Alaska was in the midst of a spring that provided snow to sea level (something we had lacked for at least two seasons prior) and reports were flooding in about good conditions on the classic backcountry nordic ski traverse: “Arctic to Indian.” This prompted me to re-assess the map: maybe there was a better way to access The BRO. Surely enough, with enough snow to ski the trail from Turnagain Arm to Indian Pass, the Indian Creek trail provided very reasonable access.

On March 4, 2017, with splitter bluebird skies but wickedly wind-blasted snow, I convinced Randoman and a visiting Randoist brethren from the Wasatch (the Salt Lake City Viking) to explore the area. Adventure in an obscure zone, epic views, and character-building snow were guaranteed. On this attempt, we were able to ski the entire route (to and from the car near sea level). As I’d done the Arctic to Indian traverse multiple times, and Randoman had completed it once, we definitely noted how much better the descent from Indian Pass was with AT gear (rather than with yard-sale inducing nordic skis matched with soft boots and NNN bindings).

Widely propagating wind slab on the south face of Bidarka on the approach:

Randoman & SLC Viking overlooking a tributary valley to Indian Creek at the pass the drops down to the base of BRO’s north face (note the classic Western Chugach surface conditions):

Randoman (The Wing is directly above is head, and Shaman Dome to the left) and Dr. FRangeLove (with the striking west face of The Beak behind him) at the pass that provides best access to north BRO:

Heading up a warmup couloir before our first attempt at the BRO:

Despite the early spring conditions providing great trail conditions in the Indian Creek valley, the mountain slopes were windblasted and punchy or slide-for-life. Combined with some old (but still spooky) pockets of hollow wind slab, a cornice fall crater just below the crux of the BRO, and route-finding issues on a complex and steep face that’s a big step up (in terms of alpine climbing) from Ptarmigan’s north face classic (the S-Couloir); we only climbed and skied ~75% of The BRO on this attempt.

Heading up the BRO:

A month and a half later (April 19), I was back for a second attempt. While much of the snowpack on the Indian Valley trail had burnt off, and required hiking in trail runners for a bit, upper elevation snow conditions were much more appealing than on the previous visit and snow stability was more confidence inspiring.

South Bidarka featured wind slabs in March, wet slabs in April:

I boogied up and over to the north face, and got into the business:

As mentioned, there’s some route-finding on the big north face to piece together a continuous line of snow. Having chosen the wrong fork on the prior attempt with the boys I went directly up the other fork this time and was handsomely rewarded (after passing through an un-skiable choke) with a big, exposed, and STEEP upper face leading directly to the eastern summit ridge just a short distance from the summit itself. A raven auspiciously greeted my arrival.

As I stared down the line, after booting up to the summit and back to the ski drop-in, I realized I had “learned to stop worrying and love the exposure.” Dr. FRangeLove was born. Not that it still wasn’t an intense vision quest experience…

In the spring of 2017, the narrow choke and crux of the line was un-skiable: too narrow for even my 171cm skinny spring skis and only filled in with rotten snow over steep rock. A short down climb with the ice tool and crampons was in order. Then, the final STEEP couloir section of the descent. The ambiance of this line is absolutely world-class, and the entire route is a testament to the wonders of ski alpinism hidden in the Western Chugach.

After bagging The BRO with sublime snow conditions, and plenty of time remaining before the exit would be rotten, more exploration was in order. I headed back up a nook in the north face to check out another potential line I noticed with the boys on the last trip. It looked like it might just be a big apron with a short chute above, but it turned out to be a wide chute into a narrow twisting couloir that snaked up the north face to the western summit ridge far higher than I could have imagined (see the video). Quite the surprise! The zone is stacked with “extreme” ski descents.

As far as I can tell, this route on the north face of BRO to the summit was both a first ascent and descent.

A compilation video from both 2017 trips (originally created for a Mountaineering Club of Alaska presentation on ski alpinism in the Western Chugach):

Skiing is dangerous, and backcountry skiing is even more dangerous. Extreme steep skiing involving alpine climbing involves consequences that include serious injury and death. Objective hazards (e.g. avalanche danger and rock fall) may be present, and the consequences of a fall or subjective (e.g. decision-making) mistake could be fatal. You are responsible for your own safety. The decision to pursue an objective like what’s discussed above cannot be taken lightly; it takes years of gaining knowledge and experience to pull it off.