Skiing is dangerous, and backcountry skiing is even more dangerous. Extreme steep skiing involving alpine climbing involves consequences that include serious injury and death. Objective hazards (e.g. avalanche danger and rock fall) may be present, and the consequences of a fall or subjective (e.g. decision-making) mistake could be fatal. You are responsible for your own safety. The decision to pursue an objective like what’s described below cannot be taken lightly; it takes years of gaining knowledge and experience to pull it off.

The Front Range of Chugach State Park, or the Western Chugach (or simply the Chugach), is often referred to locally simply as the “Front Range.” Its colloquial usage is often frustrating. For example, the Chugach National Forest Avalanche Information Center (as part of their refusal to acknowledge the Anchorage Avalanche Center as a viable winter backcountry information resource for Chugach State Park for more than six seasons now, despite their having a primary role in the development of the thesis project that became the Anchorage Avalanche Center…politics and egos) hosted public observations for the entire Western Chugach under the “Anchorage Front Range” heading for years. They only recently (2018) corrected the misnomer, and have changed that heading to the more appropriate “Chugach State Park.”

Despite my urging them to correct the misnomer for a few seasons before they finally did, it’s not really a surprise given their staff’s very limited experience with and knowledge of the Western Chugach (for two of their forecasters, limited experience in the Alaskan backcountry [outside of their forecast zone] in general); their focus is on federal land in the Turnagain Pass and Summit Lake areas of the Kenai Mountains, and to a lesser degree a small portion of the Western Chugach around Girdwood that is also United States Forest Service managed public land. As a side note, it’s odd that this avalanche center is now trying to go by the name “Chugach Avalanche Center” given that they forecast for the Kenai Mountains. Much more of the Chugach avalanche forecast is provided by the Anchorage Avalanche Center, Valdez Avalanche Center, and Cordova Avalanche Center.

Don’t get me wrong, the Friends of the Chugach National Forest Avalanche Information Center (F-CNFAIC) are an extremely well-organized non-profit with very dedicated and skilled volunteers (a model 501c3 in terms of organization, and minus the politics). The forecasters at the Chugach National Forest Avalanche Information Center (CNFAIC) do an excellent job providing technical expertise for their forecast area, and countless avalanche education opportunities. They run an undoubtedly top-notch avalanche program, but overstep their bounds when it comes positioning themselves as THE backcountry snow and avalanche authorities in Southcentral Alaska.

They preside over the Southcentral Alaska backcountry snow community with an iron fist, are intolerable of dissent, and foster a groupthink attitude that negates individual autonomy and independent thinking. They are a controlling clique, and have many times proved themselves to be exclusive rather than inclusive. I was on the board of the Alaska Avalanche Information Center (AAIC) for over three years, witnessed this exclusivity many times, and continue to witness it (a recent example being their continued exclusion of the AAIC from being a partner in the organization of the Southcentral Alaska Avalanche Workshop).

This has been an EXTREMELY stifling factor for our community. They make progress each season in many ways but not as much as they could, and many regions suffer in terms of avalanche information and education because of it. Despite the CNFAIC once having as a stated goal providing avalanche information for Chugach State Park, and playing a key role in the initial formation of the thesis project that developed into the Anchorage Avalanche Center, they’ve worked tirelessly against the Anchorage Avalanche Center for egotistical and political reasons. Their most recent stance (in response to this letter) is that the Anchorage Avalanche Center should change its name (to something other than “avalanche center”), only exist as a “skiing blog,” and observations for the area should be sent to the CNFAIC and hosted on its website (despite them having no plan for developing a program for the area and providing more than just public observations).

Maybe this would be understandable if it was the same ideology applied to the Hatcher Pass Avalanche Center (HPAC), but it wasn’t. Until the HPAC began raising many thousands of dollars more per season than the Anchorage Avalanche Center it provided an inferior product, but has always had CNFAIC support. However, HPAC is another story (too much tangent here already). I wonder, though, if the public would donate as much to the HPAC if they knew that its director and lead forecaster is only around for about half the season, and leaves for the prime of snow season to heli-ski guide in Valdez.

Let it be known that I have my faults, too. Nonetheless, this is the freest land in the land of the free. Free thinking is the foundation of our great nation. The Anchorage Avalanche Center has become an expression of freedom.

A few more things about the “Front Range,” and then on with the trip report:

More generally, and adding to the frustration, “Front Range” is often used by many misinformed locals to refer to all of Chugach State Park (or the Western Chugach, which is mostly Chugach State Park – i.e. public land managed by State of Alaska Department of Natural Resources). I’m diligent in my efforts to improve the local culture regarding mountain nomenclature. The Chugach Front Range “consists of the peaks encircled by a line traveling along Turnagain Arm, Indian Creek, Indian Creek Pass, the South Fork of Ship Creek, Ship Creek, Knik Arm, Cook Inlet, and Turnagain Arm” (Mountaineering Club of Alaska).

In other words, once you’ve passed Indian Creek heading SE on the Seward Highway toward Girdwood you’ve left the “Front Range.” Falls Creek is in the Front Range, but Bird Ridge is not. Once you’ve passed Ship Creek heading north on the Glenn Highway toward Eagle River, you’ve left the Front Range. Arctic Valley, South Fork Eagle River, North Fork Eagle River, and everything north of Ship Creek (even the peaks directly above the highway like Baldy and Bear Mountain) are not “Front Range.” These areas are more appropriately referred to as “Chugach State Park” or “Western Chugach.”

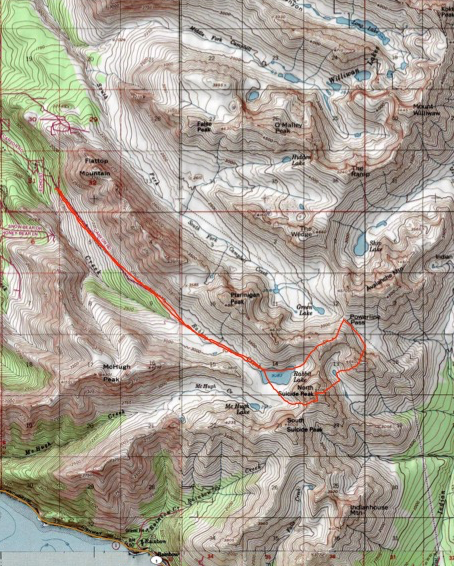

That said, back to the trip report. My point with the tirade about “Front Range” is that this trip report is about my favorite line in the Front Range proper (not all of the Western Chugach or Chugach State Park): the NE couloir of North Suicide Peak. It should be mentioned that North Suicide Peak, much like Ptarmigan Peak, is one of the best peaks to play on in Anchorage’s backyard mountain playground. It holds a few absolutely world class steep ski descents: the NW face (seen here), the SW face (on the summit ridge just north of the summit here, Gnarly Noodler dropping in just below the summit here, Gnarly Nooder steazing the upper SW face here), and the NE couloir. As of the spring of 2018 I’d skied the NE couloir three times. My first time was, hands down, the best. Despite the line being north facing, the HUGE walls that frame it get covered in rime and snow and have some solar exposure, which shed into the NE couloir once spring arrives. Both times I’ve skied the line in April it has been almost entirely slide-for-life and with either a downclimb at the crux, or a section of thin side-stepping with ice axe/tool sticks.

As of the spring of 2018 I’d skied the NE couloir three times. My first time was, hands down, the best. Despite the line being north facing, the HUGE walls that frame it get covered in rime and snow and have some solar exposure, which shed into the NE couloir once spring arrives. Both times I’ve skied the line in April it has been almost entirely slide-for-life and with either a downclimb at the crux, or a section of thin side-stepping with ice axe/tool sticks.

This trip report is about a descent of the NE couloir on February 25, 2017 with Sam Inouye and Brian “Randoman” Harder. We had a nearly full Randoist Posse (minus Travis Baldwin), and were prepared with nearly all of the tricks-of-the-trade (harness, rope, pitons, ice tool w/hammer, etc.) With a bit of fresh snow and in late February conditions with no sun-affected snow, the line was thoroughly prime. The NE couloir of North Suicide was just the start. We completed a linkup that also included the north couloir of Homicide Peak and SW face of South Powerline Peak.

Mat and Sam near Rabbit Lake on the approach (North suicide left, South Suicide right, the saddle between them is known as Windy Gap as it channels the prevailing SE winds of Turnagain Arm):

Assessing snow stability (remember this is a grassroots, volunteer avalanche center filling a void the State of Alaska and Southcentral Alaska avalanche professionals have not addressed; often personal objectives provide field data for avalanche advisories) at the base of the prominent (and relatively low angle) SW couloir of North Suicide that provides best access to the NE couloir:

Climbing the SW couloir of North Suicide to access the NE couloir (Windy Gap, Hauser’s Gully, and South Suicide in the background of photo 1):

Mat and Sam on the summit ridge just south of the summit:

After tagging the summit (Sam hadn’t stood on it before), we down-climbed back to the couloir entrance and found a rock horn anchor to belay me (Mat) into the couloir for stability assessment. While not the technical crux of the route, the entrance is a big and steep slope that funnels into a narrowing and twisting couloir. An error in stability assessment would be catastrophic, as even a small avalanche (or sluff) that causes a loss of control could prove fatal given that the line is over 1800′ feet with exposure at the narrow crux and abruptly walled-in (which could provide for a brutal pinball effect). See the video around the 2 minute mark for this section.

About a third of the way down the line the couloir twists from north to east, and this is the crux: a cliff section (at least in both the 2017 and 2018 snow seasons) provides only a narrow egress on the skier’s right. In February 2017 it was ski-able, but less than 200cm wide. In late April of 2017, it was too icy and thin (scraped and scoured from the shedding rock walls above) to even be side-stepped and was down-climbed with an ice axe (an actual ice tool would have been more comforting) and crampons. Earlier in April (of 2018), it was side-step-able but those side-steps were accompanied with ice tool sticks in the very firm snow.

Randoman got first looks in February 2017 (his excitement is apparent):

I guess, given that I did all the research, I deserved first licks:

A couple photos looking back at the line:

From the base of North Suicide’s NE couloir, we headed up the SW couloir of Homicide (as seen from near the summit of North Suicide in photos 1-2):

With the first big question of the mission (does the NE couloir of North Suicide “go” as a ski descent) answered, we were about to answer the second big question (what does the N couloir of Homicide entail):

Unless you can huck a 20′ cliff into a couloir less than 180cm wide in places and straight-line 45-50 degree snow for over 1000′, it entails a short down climb from the col and a rappel (Mat and Sam post-abseil):

Sam, with the shortest skis, steazes the crux:

I got sloppy thirds on this one, and with the longest skis (175cm) of the group was just barely able to squeeze through the choke with tips and tails scraping the walls after the snow had been scoured down a bit by Brian and Sam:

As it widened back out to 180+cm, I was able to get my turn on:

Looking back at Homicide’s north couloir from its base a few hundred feet below Powerline Pass:

Sam at Powerline Pass about to head up the NE ridge of South Powerline Peak in order to ski its SW face back to Rabbit Lake for our egress and completion of this fine lollipop tour:

Video of the day (originally prepared for a Mountaineering Club of Alaska presentation on ski alpinism in the Western Chugach):